VITRUVIANO

Januario Jano

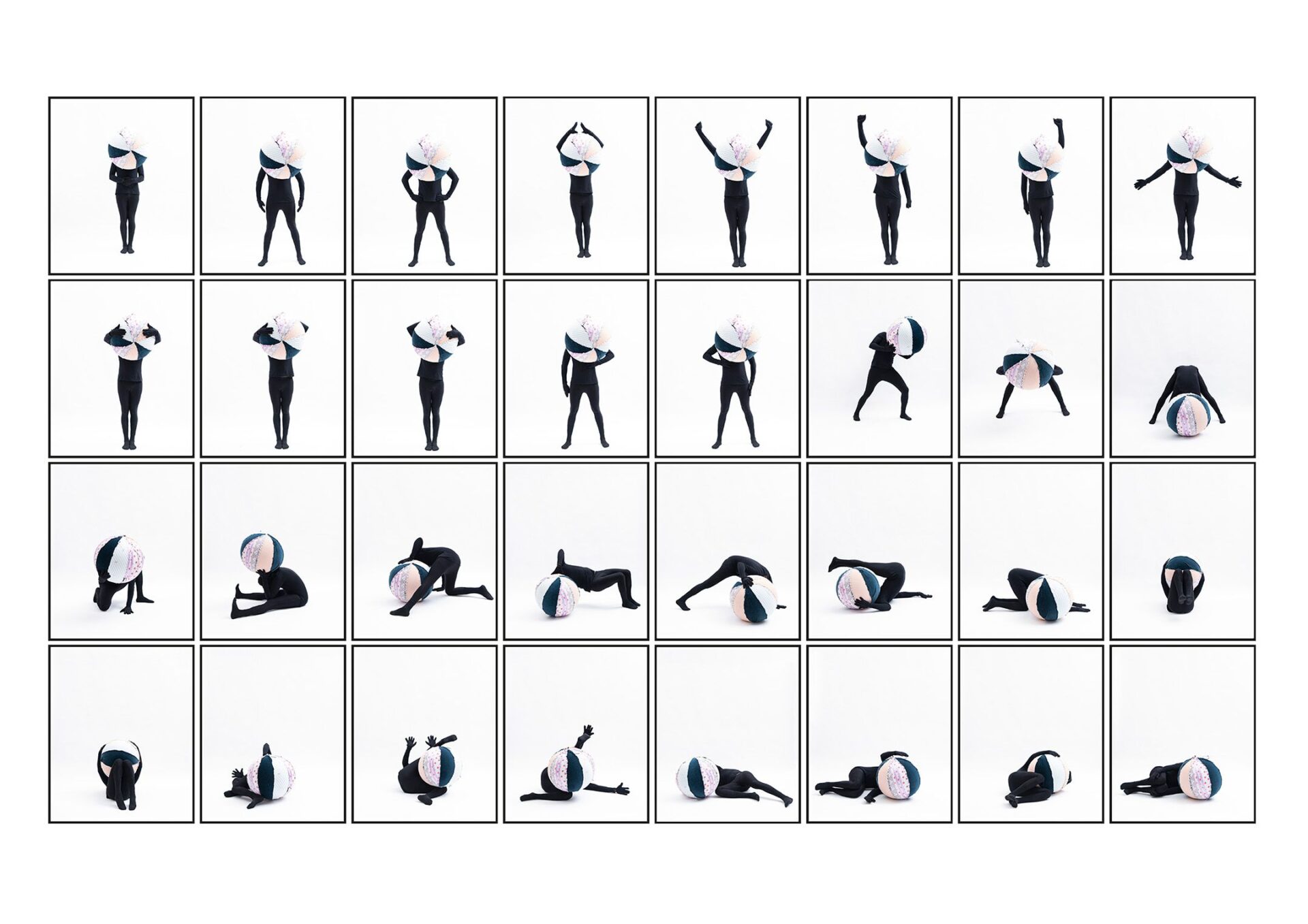

Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Vitruvian Man’ is the epitome of the set of laws-emblem of the European Renaissance man with which his self-consciousness culminates, by force of all the knowledge collected, the aesthetic, intellectual, scientific, cultural and artistic improvement, to feel himself the centre of the world. It also implies the process explained by the metaphysical theories that study the phenomenon of perception and the essence of existence, by which each human consciousness places itself at the centre of its perceptual reality and, detached from there, its material reality (Strongman, 2010). We see in the photographs that make up ‘Vitruviano’ an element of play and subversion to detract from the solemnity of this archetypal image and question these two connotations.

The first of these is linked to the hegemonic version of the fundamentals of history that we learn as universal truths, but which are really subject to the transcendence of certain capsules of power, politics and geography, and exclude other readings and other pieces of knowledge not yet postulated, or those that are made invisible either because of their dissidence or their lack of interest in the dominant cause. The second could be the reason that explains the Western dialectical tendency to hierarchise subjectivities, imposing some over others. Januario’s work seeks to question these codes by opening up a space for debate on this sense of self-importance of the single narrative and its homogenising projection, which is legitimised by an accumulation of knowledge that is reductive to its own operative context and exclusive of others, indicating that there are as many realities as subjectivities and, by metaphysical explanation, as many subjectivities as individuals, thus disabling in his work the simplicity of a single reading and addressing the active role of the subject-spectator.

On the other hand, in Jano’s work the body and the sense of ‘embodiment’ (corporeal materialisation) linked to it, are the vehicle for questioning and destabilising the narratives that start from the perception, analysis, definition, domestication and codification of the body in order to situate it in society, while also connecting body and space, alluding to the aesthetic and experiential exchange between object and subject.

As the artist declares, he navigates his own memories in an attempt to manage unresolved emotions, in a search for a sense of place and belonging – concerns typical of the migrant subject, as marked by his biography, which transits between Luanda, Lisbon and London. From the entrails of these memories emerge colonial subjectivities and traumas linked to them that he seeks to heal, but also concerns that transcend ‘geographical, temporal and spatial limits’ (Januario, 2023). Thus, the universality of what the artist defines as a central element in his work converges in the personal: the concept of displacement, between meanings, between cultures, between systems of representation and the construction of images, since, as we can affirm, culture is in itself a migrant subject.

In one of its definitions, ‘the image is the visible form that relates to a past, present or future experience’ (Pepa Medina, 2012). If in the pictorial and symbolic image (that which represents abstract things and whose value is defined pragmatically in society as Rudolf Arnheim explained) of the Da Vinci’s ‘Vitruvian Man’, it is also said that the circle that circumscribes the man as the measure of all things connotes a fourth representative dimension that would be time – specifically, its infinity (Strongman, 2010), In Januario’s work, time is the framework on which the objects and artefacts that construct the different narratives on which the stratified stories that end up defining history are erected and selected, which the artist exemplifies with the superimposition and interweaving of found objects, textiles, images and other materials from his own and others archives, in a circularity between the historical and the contemporary, are sedimented. In these compositions, meaningful connections between seemingly disparate elements and temporal crossovers eventually emerge, as if by force of the unconscious or an echo of the ‘Atlas Mnemosyne’ proposed by the historian Aby Warburg, as a network of never-conclusive relationships between images. For instance, with the use of cotton as a medium for photographic printing, Januario pays homage to the textile traditions of the Ambundu communities of Angola and denounces how these were lost through the imposition of Portuguese colonial practices, which sought to homogenise the identity of the people so that Christian ideology and extractive wage labour.

As Januario Jano concludes to explain the process of creating the works, in intricately intertwining artefacts, materials and meanings, “These artistic gestures create a platform for an immersive exploration of the intricate relationship between the body and space over time. They beckon viewers to engage with the rich tapestry of history, culture, and identity interwoven within each piece”.

Carmen Bioque, 2024

Bibliografía:

Januario Jano (2023)

Pepa Medina (2013). ‘La imagen como signo y como símbolo’. Las Nubes. Revista de filosofía, arte, literatura

Strongman, L. (2010). ‘Force Field: Vitruvian Man and the Physics of Sensory Perception’. International Journal of Arts and Sciences 3(9) 218-226. ISSN: 1994-6934